Contributed by Elaine Quinn, editor of The Conscious Lawyer

Contributed by Elaine Quinn, editor of The Conscious Lawyer

This review first appeared in the online magazine, The Conscious Lawyer, vol IV, October 2018.

You can purchase this book through Routledge Taylor & Francis Group or through your favorite bookseller.

“…our original longing from birth [is] to be seen by the other in a way that fully recognizes our humanity and our longing to simultaneously affirm our recognition of the other in the same way.” (Chapter 3, page 58)

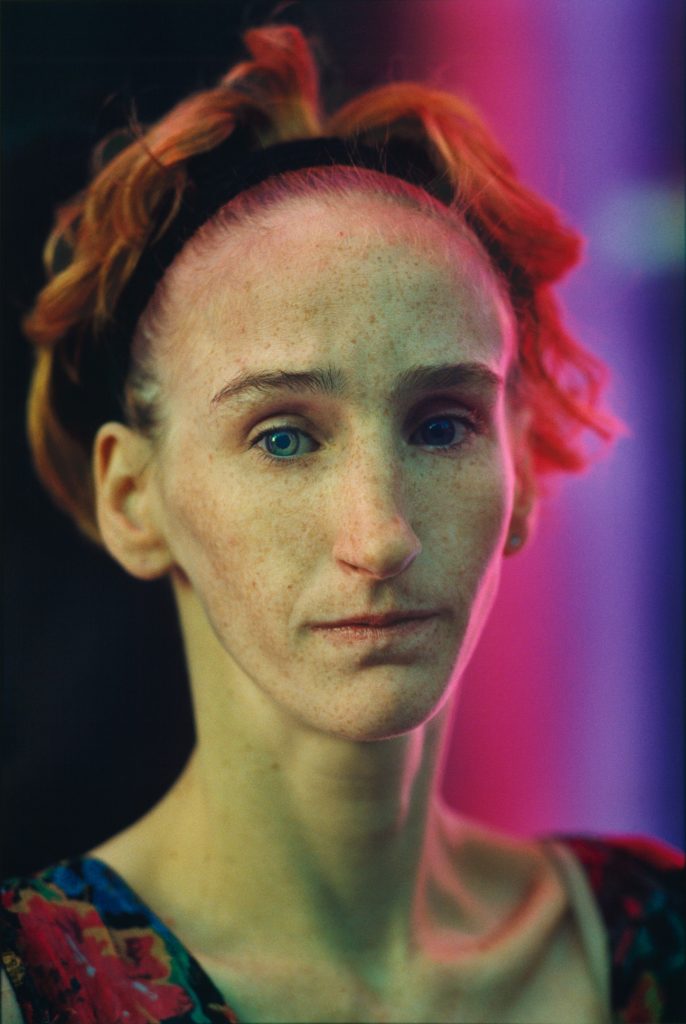

Before reading any further, take a moment to sit and look at the striking portrait below. This unusual and powerful invitation is one made to the reader in the first chapter of the book.

© Robert Bergman, all rights reserved. www.therobertbergmanarchive.org/h6>

It is an invitation that perhaps experientially captures the essence of what the author wants to convey – the experience of being truly recognized by a fully present human being, of deepening into our own natural presence as a result, and the subsequent implications for our collective reality were this to be become a more consistent experience for all of us. In ‘The Desire for Mutual Recognition’, Gabel attempts to unravel, in a spiritually-aware yet deeply grounded way, the knots of why this apparently most natural of states is so rare for human beings today and why its re-emergence is critical. An author interview that supplements and extends the ideas described in this book review, particularly for lawyers, can be found in The Conscious Lawyer vol IV.

The book is organized into ten chapters spanning, firstly, an exploration of the human desire for mutual recognition and how that desire gets thwarted and suppressed from the moment we are born to, secondly, a thorough examination of this social phenomenon in our collective society — how it manifests in our language, thought and ideology; our community structures from family to nations; and its deep problematic effect on our systems of economics, law and politics – to, finally, the book’s last chapters which offer insightful and practical wisdom toward understanding and rediscovering our truth, not as an individual endeavor, but with and for each other, and our world’s, future.

For the legal community, the book in its entirety is well worth reading for an understanding of the wider social vision within which law gains its meaning. Chapters 5 and 7 however deal particularly with how the book’s main thesis manifests within the field of law.

So, what is the root of our challenge in our mutual recognition of one another? We all know the beautiful sense of openness and transparency from a new born baby willing and unafraid of connecting innocently with the world around it. The baby enters a world however that is heavily conditioned with centuries of suffering and contraction. Gabel describes this as the “cultural envelope” of our time and it immediately casts its shadow over the baby and child, initially through parents and families (the “psycho-spiritual field” we grow up in), and eventually through wider society. We learn that it is safer and indeed a “condition of social membership”, to contract, close and become absent rather than present. The extent to which this happens, in Gabel’s view, will depend on our experience of authentic social presence from those around us growing up.

Poignantly, not only does the child learn to withdraw and contract, it also learns to act as though this contracted self is who it really is, in effect cementing it into a growing sense of separation from its true self and others. A striking, almost caricature-ish, US newscaster motif illustrates this aspect of our nature well. A living human being like the rest of us but cloaked in his “newscaster” performance Gabel says of him: “…the key point that I am making about the newscaster here is not to single him out for his alienation, but to describe in a recognizable way the outer “casting” of the self, the transformation of our being into alienated performances, which occurs not just in the extreme case of the newscaster, but is suffered by all of us.”

Inevitably then, this sense of individual withdrawal and separation impacts upon our collective existence in myriad ways. Instead of perceiving our “horizontal existential reality”, the “living latticework of inter-being” within which we exist, we become “frozen into falsehood” and “we float in each other’s presence rather than exist fully in the presence as the ground of our being”. Gabel takes us on a fascinating journey of how this phenomenon manifests in our culture and society through language, thought and ideology; family (often “incubators of alienation for each new generation”), communities, work and various governing system dynamics.

Difficulty in understanding and perceiving this state of affairs, he says reassuringly, is completely normal. We are so much “inside of it”, it can be difficult to imagine any alternative. In Chapter 5 however, we are asked to cast our minds back 500 years and perhaps contemplate the feudal hierarchy that existed then. We likely have no difficulty in accepting that the oppressive and limiting hierarchies and power structures that existed at that time were unnatural and unnecessarily constrictive to human beings. Can we accept that our descendants may see our times in the same way?

The import of Gabel’s thesis has particular significance for those of us working in law. In a courageous metaphor, Gabel says: “the entire, majestic “legal order” — “The Law” itself — is a vast and elaborate acting out of the Emperer’s Clothes story”. The parallels between that fairy-tale and the laden-down imagery and concepts in our legal systems today are compelling. Law, Gabel says, is the most legitimating ideology of the status quo because it solidifies into concrete norms, rules and laws the way human beings interact and relate. If, as has been described, we are interacting and relating predominantly through false selves, then we must acknowledge that the law itself is one of the prime agents keeping us locked in. Unfortunately, these revelations can be deeply threatening to the constructs of our legal and justice systems as they speak to the core of their very foundations.

“We suddenly experience ourselves as actually existing, the world fills out like a great balloon of horizontal presence and mutuality, and the spiritual radiance that had previously been contained through collective social withdrawal suddenly becomes visible, illuminated.” (Introduction, page 4)

While the book is a serious and incisive critique of the human social landscape, it is by no means pessimistic. Through understanding clearly where we stand and why we suffer, great hope is possible. Gabel believes that “social movements are the vehicle for our evolution”, they are “liquefying movements” for our frozen world. Within them, however we now need a new ‘socio-spiritual activism’ to heal the fear at the heart of our own beings individually and collectively in order to breathe enough confidence into our movements toward each other and out into the world.

In the final chapter of the book, three “levels” of practice, or circles of beingness, from the individual to community to world offer grounded, practical wisdom for those committed to the task of healing and repairing our “life-world”. Gabel is careful to emphasise that these practices must be lived and not adopted as a method to fixing a world separate and “outside of us”. Our social being, Gabel says, is ontological and trans-historical. We must then become grounded together in our beings and co-create a parallel world that reflects this.

In the innermost circle, we begin to heal our separation through surrendering our detachment, using meditation and contemplative practices of our choice, enabling us to move outward toward others with courage and truth. Ways of speaking and writing that describe our being-in-the-world are emphasised, a marked feature of Gabel’s own writing in this book and other publications. This practice alone, if adopted within legal education, could represent a radical shift given how entrenched is our detached way of writing and speaking about the world.

In the second circle, we progressively begin to have steady healing encounters of authentic social presence with and through others, seeking out rich social locations where this is encouraged. Locations for religious or spiritual worship; local neighbourhoods, farmers markets; unions or even our families offer possibilities for these encounters. For lawyers, there are collective initiatives described in the magazine that can also offer this possibility.

In the third circle, we begin to weave a new narrative about the world which are drawing towards us through engaging in these practices. This is “the more beautiful world our hearts know is possible” evoked by Charles Eisenstein in his book of that title. Gabel cites Martin Luther King Jr. as “an example for what we all should aspire to as rhetoricians and prophets, as evokers of the world we seek to ring into being.”

I found ‘The Desire for Mutual Recognition’ to be really a profoundly illuminating book for lawyers and non-lawyers alike. It is rich and dense in its insight and it is impossible to do it justice in a short review. I wholeheartedly recommend it hope there will be a time in the near future when it will be recommended reading for new lawyers – the ones bravely envisioning, living, and slowly realizing this new legal culture we are dreaming of.

“The bodies relax, the collective vigilance abates, the destinations lose their urgent character, and we emerge into each other’s company, relieved at our suddenly being-here and being alive, instead of determinedly not being-here and having to be muted and withdrawn.” (Chapter 3, page 59)